There are so many basic plots—ready to simply snatch as I’ve recently learned—but I’ll be damned if I can write a good one.

There are so many basic plots—ready to simply snatch as I’ve recently learned—but I’ll be damned if I can write a good one.I’m not sure why I try. It’s a pity we’re not living in a more nouvelle roman era—since I specialize in what might be called the meandering existential novel, sans epiphany, sans much of anything but a lot of moping about—but we’re living in the age of increasingly short attention spans, data smog, and well, the overwhelming popularity of new narratives, such as video games, that are much more viscerally arresting. Let's be honest.

I should ask, “Who needs plot, not to mention text?” and be done with it. But I like plot. And I like text.

Despite the slipping and sloping and pausing, the attempted dipsy-do’s and dipsy-don’ts, the outright boring and embarrassing maudlin pitches of my writerly sensibilities, I relish a good plot. I envy writers who can write good plots like I envied guys who could get dates in high school (is there a connection between the two?).

I also hate writers who can write good plots, just as...yes, of course.

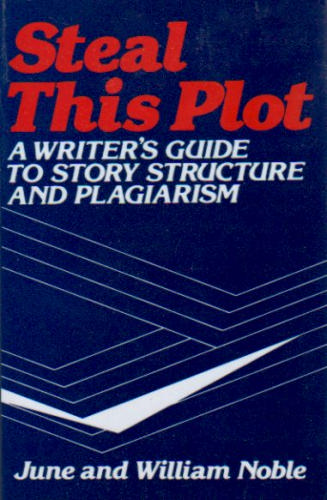

So, after all of these years of reading relatively serious fare (Roland Barthes anyone?) I picked up Steal This Plot, by June and William Noble, in a dog-eared, nearly bankrupt used book store, and it turned out to be one of the better "how-to-write" books I’ve read.

The caveat is that very few in the literary how-to genre have done me much good. Steal This Plot at the very least offers some archetypal plot structures to consider when writing any story. You don't have to steal the plot so much as you can think about the tendencies of your own storyline and consider the trajectory of other stories. If you're an undisciplined writer, and one who prefers to write without an outline, then Steal This Plot will surely help bring discipline to your storyline, and perhaps tame any wild tangents.

With its distinctions between plot spicers and plot motivators, it offers even experimental writers something to think about when constructing a narrative. I have to say that I think this book if more helpful than Francine Prose's Reading Like a Writer.

Here are the plot motivators:

- vengeance

- catastrophe

- love and hate

- the chase

- grief and loss

- rebellion

- betrayal

- persecution

- self-sacrifice

- survival

- rivalry

- quest

- ambition.

- mistaken identity

- criminal actions

- deception, honor

- increase or decrease in material well-being

- authority

- making amends

- conspiracy

- rescue

- unnatural affection

- suspicion

- suicide

- searching.

Good plots can be told repeatedly in endless variations, I hear.

I recently read

I recently read